One of the big announcements at ng-conf this week was the collaborative work that the Angular and TypeScript teams have been doing. Angular 2 will leverage TypeScript heavily and you can as well in any type of JavaScript application (client-side or even server-side with Node.js). You can also use ES6 or ES5 with Angular 2 if you decide that TypeScript isn’t for you. Andrew Connell and I gave a talk on TypeScript at ng-conf that you can view here if interested:

I’ve been a big fan of TypeScript for many years and decided to update a few previous posts I’ve done to help people get started with it. In this first post I’ll talk about the basics of TypeScript and provide additional details about the language in future posts.

TypeScript Overview

Here’s what the TypeScript site (http://typescriptlang.org) says about TypeScript:

TypeScript lets you write JavaScript the way you really want to.

TypeScript is a typed superset of JavaScript that compiles to plain JavaScript. Any browser. Any host. Any OS. Open Source.

TypeScript was created by Anders Hejlsberg (the creator of the C# language) and his team at Microsoft. To sum it up, TypeScript is a language based on ES6 standards that can be compiled to JavaScript. It isn’t a stand-alone language that’s completely separate from JavaScript’s roots though. It’s a superset of JavaScript which means that standard JavaScript code can be placed in a TypeScript file (a file with a .ts extension) and used directly. That’s a very important point/feature of the language since it means you can use existing JavaScript code and frameworks with TypeScript without having to do major code conversions to make it all work. Once a TypeScript file is saved it can be compiled to JavaScript using TypeScript’s tsc.exe compiler tool, by using a variety of editors/tools, or by using JavaScript task runners such as Grunt or Gulp.

TypeScript offers several key features. First, it provides built-in static type support meaning that you define variables and function parameters as being “string”, “number”, “boolean”, and more to avoid incorrect types being assigned to variables or passed to functions. Second, TypeScript provides a way to write modular code by directly supporting ES6 class and module definitions and it even provides support for custom interfaces that can be used to drive consistency. Finally, TypeScript integrates with several different tools such as Brackets, Sublime Text, Emacs, Visual Studio, and Vi to provide syntax highlighting, code help, build support, and more depending on the editor. Find out more about editor support at http://www.typescriptlang.org/#Download. In addition to all of this, TypeScript supports much of ES6 (with more and more ES6 features being added in each release) and also includes support for concepts such as generics (code templates), interfaces, and more.

TypeScript can also be used with existing JavaScript frameworks/libraries such as Angular, Node.js, jQuery, and others and even catch type issues and provide enhanced code help as you build your apps. Special “declaration” files that have a d.ts extension are available for over 300 frameworks/libaries and with the latest announcement at ng-conf by the Angular and TypeScript teams I fully expect that number to go even higher. Visit http://definitelytyped.org to access the different declaration files that can be used with tools to provide additional code help and ensure that a string isn’t passed to a parameter that expects a number. Although declaration files aren’t required, TypeScript’s support for declaration files makes it easier to catch issues upfront while working with existing libraries such as Angular and jQuery.

Getting Started with TypeScript

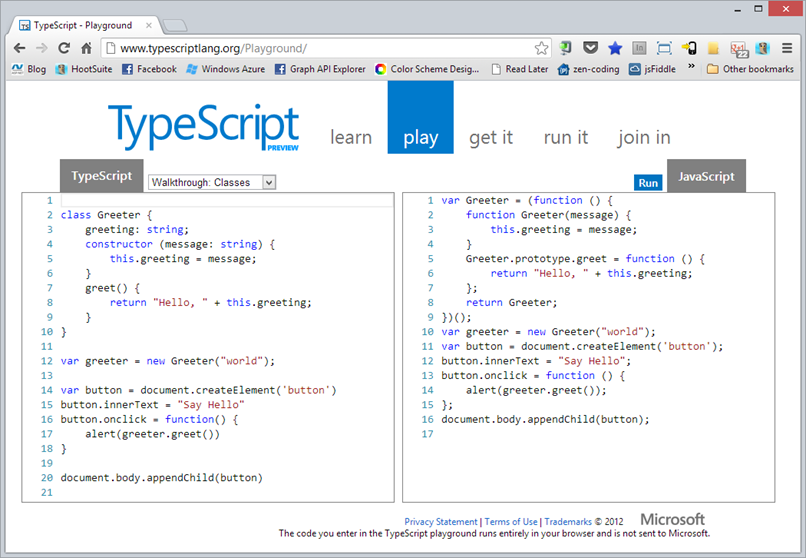

To get started learning TypeScript visit the TypeScript Playground available at http://www.typescriptlang.org. Using the playground editor you can experiment with TypeScript code, get code help as you type, and see the JavaScript that TypeScript generates once it’s compiled. Here’s an example of the TypeScript playground in action:

One of the first things that may stand out to you about the code shown above is that classes can be defined in TypeScript. This makes it easy to group related variables and functions into a container which helps tremendously with re-use and maintainability especially in enterprise-scale JavaScript applications. While you can certainly simulate classes using JavaScript patterns (note that ECMAScript 6 will support classes directly), TypeScript makes it quite easy especially if you come from an object-oriented programming background. An example of the Greeter class shown in the TypeScript Playground is shown next:

class Greeter { greeting: string; constructor (message: string) { this.greeting = message; } greet() { return "Hello, " + this.greeting; } }

Looking through the code you’ll notice that types can be defined on variables and parameters such as greeting: string, that constructors can be defined, and that functions can be defined such as greet(). The ability to define types is a key feature of TypeScript (and where its name comes from) that can help identify bugs upfront before even running the code. Many types are supported including primitive types like string, number, boolean, array, and null as well as object literals and more complex types such as HTMLInputElement (for an <input> tag). Custom types can be defined as well.

The JavaScript output by compiling the TypeScript Greeter class is shown next:

var Greeter = (function () { function Greeter(message) { this.greeting = message; } Greeter.prototype.greet = function () { return "Hello, " + this.greeting; }; return Greeter; })();

Notice that the code is using JavaScript prototyping and closures to simulate a Greeter class in JavaScript. The body of the code is wrapped with a self-invoking function to take the variables and functions out of the global JavaScript scope. This is important feature that helps avoid naming collisions between variables and functions.

In cases where you’d like to wrap a class in a naming container (similar to a namespace or package in other languages) you can use TypeScript’s module keyword. The following code shows an example of wrapping an AcmeCorp module around the Greeter class. In order to create a new instance of Greeter the module name must now be used. This can help avoid naming collisions that may occur with the Greeter class.

module AcmeCorp {

export class Greeter {

greeting: string;

constructor (message: string) {

this.greeting = message;

}

greet() {

return "Hello, " + this.greeting;

}

}

}

var greeter = new AcmeCorp.Greeter("world");

In addition to being able to define custom classes and modules in TypeScript, you can also take advantage of inheritance by using TypeScript’s extends keyword. The following code shows an example of using inheritance to define two report objects:

class Report { name: string; constructor (name: string) { this.name = name; } print() { alert("Report: " + this.name); } } class FinanceReport extends Report { constructor (name: string) { super(name); } print() { alert("Finance Report: " + this.name); } getLineItems() { alert("5 line items"); } } var report = new FinanceReport("Month's Sales"); report.print(); report.getLineItems();

In this example a base Report class is defined that has a variable (name), a constructor that accepts a name parameter of type string, and a function named print(). The FinanceReport class inherits from Report by using TypeScript’s extends keyword. As a result, it automatically has access to the print() function in the base class. In this example the FinanceReport overrides the base class’s print() method and adds its own. The FinanceReport class also forwards the name value it receives in the constructor to the base class using the super() call.

TypeScript also supports the creation of custom interfaces when you need to provide consistency across a set of objects and ensure that proper types are used. The following code shows an example of an interface named Thing (from the TypeScript samples) and a class named Plane that implements the interface to drive consistency across the app. Notice that the Plane class includes intersect and normal as a result of implementing the interface.

interface Thing { intersect: (ray: Ray) => Intersection; normal: (pos: Vector) => Vector; surface: Surface; } class Plane implements Thing { normal: (pos: Vector) =>Vector; intersect: (ray: Ray) =>Intersection; constructor (norm: Vector, offset: number, public surface: Surface) { this.normal = function (pos: Vector) { return norm; } this.intersect = function (ray: Ray): Intersection { var denom = Vector.dot(norm, ray.dir); if (denom > 0) { return null; } else { var dist = (Vector.dot(norm, ray.start) + offset) / (-denom); return { thing: this, ray: ray, dist: dist }; } } } }

At first glance it doesn’t appear that the surface member is implemented in Plane but it’s actually included automatically due to the public surface: Surface parameter in the constructor. Adding public varName: Type to a constructor automatically adds a typed variable into the class without having to explicitly write the code as with normal and intersect.

TypeScript has many additional language features but defining types and creating classes, modules, and interfaces are some of the key features it offers. I’ll be covering additional features in future posts so stay tuned. Subscribe to my Web Weekly newsletter (at the top of the blog or below) to stay up-to-date on all of the latest technology that I find and write about.